The Supreme Court’s decision overturning the D.C. handgun ban makes it more difficult for gun banners to do their job, at least until an anti-gun rights president is in position to appoint new justices to the court. In the meantime, the prohibitionists are implementing a new strategy—ban as many people as possible from owning guns.

The strategy has been perfected in Canada, and is now moving south of the border, perhaps coming soon to where you live. The cornerstone of the strategy is a discretionary licensing system for gun ownership.

Under existing federal law, there are millions of people who are legally banned from owning guns. These bans are based on objective criteria, such as a person having been convicted of a felony or a domestic violence misdemeanor, or having been dishonorably discharged from the military.

From the gun prohibitionist viewpoint, these objective criteria are grossly insufficient, because they still leave the vast majority of the population able to legally possess firearms. So in the effort to ban more people, the gun prohibitionists set up licensing systems that intrude into the applicant’s personal life. The purpose is to look for something—anything—that indicates, supposedly, that the applicant might misuse a gun.

For example, in Canada, an applicant for a gun permit must disclose whether he has ever filed for bankruptcy, or has lost a job. He must even provide a list of his past romantic relationships, so that the police can contact former girlfriends.

Then, if his former girlfriend or ex-boss doesn’t give him a good recommendation, his gun license will not be renewed, and any guns he owns must be surrendered.

It’s not just a problem for Canadians. Government fishing expeditions into one’s private life are now being used to implement gun control right here in the United States.

Consider Nassau County, Long Island, a populous suburban county east of New York City. The Nassau County Police Department (NCPD) oversees the issuance of handgun licenses, which must be renewed every five years. Last year, the NCPD added a new question to the application:

“Have you used or still use [sic] narcotics, tranquilizers or anti-depressant medication? If YES, record doctor’s name, address and phone number, (attach).” A list of all relevant medications is required.

In reality, these categories of drugs—narcotics, tranquilizers and anti-depressants—are so broad that almost every adult could be identified as a potentially dangerous drug user through this question.

Pain Relievers It is difficult to conceive of anyone honestly answering “no” to narcotics use since, pharmacologically, “narcotics” include the Tylenol with Codeine you might take for a toothache, or the Vicodin you might have taken to control the post-operative pain of a minor surgery.

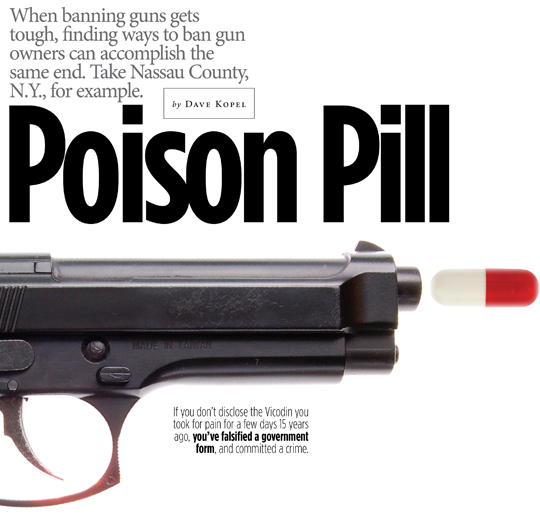

If you don’t disclose the Vicodin you took for a few days 15 years ago, you’ve falsified a government form and committed a crime. And soon enough, gun-licensing officials may have access to your prescription drug records.

Since June 2005, all New York pharm-acists have been required to electron-ically submit to the State Department of Health all the prescriptions written for drugs like these.

The Nassau County Police Depart-ment is already in routine contact with the State Office of Mental Hygiene regarding pistol license applications. We expect they will shortly be able to access the New York state drug database. They can then cross-reference it with the names of registered handgun owners to see who was prescribed medication in these categories. Anyone who has answered incorrectly would be open to prosecution for perjury.

Clearly there is no public safety need for the pistol licensing bureaucracy to demand information about a woman’s legal use of morphine when she was in a hospital 10 years ago recovering from childbirth. But if she fails to remember and to tell the police about it, then she puts her right to own a handgun at risk.

When you buy a gun in a store, you must fill out the federal Form 4473, which asks, “Are you an unlawful user of, or addicted to, marijuana or any depressant, stimulant, narcotic drug or any other controlled substance?” If the answer is “yes,” then of course you cannot buy the gun.

Notice that the federal inquiry is much narrower than the version now being used in New York. The federal form asks only about “unlawful” use or addiction.

We all know that strong pain relievers can create a feeling of pleasure, and that some people use the drugs illegally for that reason. But the NCPD is asking about legal use, not illegal use.

Pain relievers often carry warning labels, which tell patients not to drive or operate heavy machinery during use. Obviously, if you are feeling drowsy because you took some Tylenol, or just because you didn’t get enough sleep last night, you should not go hunting or go to the target range.

But when you buy a car, or heavy machinery, the government does not demand that you fill out a form detailing every instance of narcotic pain reliever use in your life. The general laws about reckless endangerment—including conduct involving the use of cars, heavy machines and firearms—already require that people who are impaired for any reason not use these powerful tools.

What about someone who uses painkillers, legally, on a daily basis? There are lots of such people. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), chronic pain is a leading cause of disability in this country. Many people require narcotic drugs on a daily basis—alone, or in combination with other medications. Do the gun control forces have a good argument that those people shouldn’t own guns?

Actually, the side effects of painkillers (drowsiness and mental pleasure) tend to disappear with continued use of the drug at the same dosage. That’s why illegal addicts (who are looking for mental pleasure, not for physical pain relief) take higher and higher doses.

Studies have found that the adverse effects of drowsiness or impaired cognitive ability are very temporary. According to a study of Finnish drivers, published in the German medical research journal Der Schmerz in August of this year, seven days after initiating opioid therapy, or after increasing the dose of opioid medication, “there was no general deterioration in patients’ driving ability.” Other medical experts have come to similar conclusions. (Rush University Medical Center, Nov. 25, 2007; “Opioids” entry in The Merck Manual—Home Edition.)

Anti-Depressants Another class of red-flag drugs on the NCPD list, anti-depressants, was found in a CDC study to be one of the most commonly prescribed types of drugs in the United States.

Although anti-depressants have very beneficial effects for the vast majority of patients, in 2007 the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) ordered warnings that advise doctors to closely monitor patients during the first two months of use. A 2005 University of Nebraska Medical Center survey found that only 7.5 percent of Nebraska doctors who prescribed anti-depressants saw their patients weekly during the first month of anti-depressant use. Hopefully, the new warning labels will lead to much more proactive monitoring by doctors.

Now suppose the police call up a doctor who has been successfully treating a 50-year-old woman for depression for the last 18 months. From a purely medical standpoint, the doctor would probably think, “I don’t think that there is any notable risk from her having a handgun.”

But if the doctor has a lawyer, the lawyer may advise, “You can’t guarantee that this woman—or, for that matter, a patient you treat for a broken leg—positively won’t do something w

More Like This From Around The NRA

More Like This From Around The NRA