Why Microstamping and

Bullet Serialization Won’t Work

A firearm examiner dispels the myths of these common gun-ban schemes being pushed in states throughout the nation.

As an independent firearm examiner, the fact that I am paid by prosecution, defense or an individual makes no difference. I work for science. My job is to find out what happened. As one who works with law enforcement, I want the bad guys punished. I also want to see the innocent freed and the law-abiding citizen unmolested by government. As a taxpayer, I want my taxes spent wisely.

Working for a government subcontractor, I personally watched millions of dollars frittered away through bureaucratic ineptitude, always with the best of “stated” intentions. Living through this made a lasting impression. With the proposed schemes of microstamping and ammunition coding, I see a plan to destroy the American ammunition industry while invigorating crime from the organized level down to the street thug.

With microstamping and bullet serialization, we face the latest schemes to evolve from what has previously been referred to as “Ballistic Fingerprinting.” This idea was to create a databank of images of the rifling striae, or marks, on fired test bullets as well as breech face signatures (impressions) and firing-pin impressions on a fired cartridge case for all new semi-auto handguns—and possibly all new guns—sold in the United States. The idea would be to include these images for comparison with crime-scene ammunition evidence entered into the current computer system using the Integrated Ballistic Identification System (IBIS), which is the actual hardware and software system used under the National Integrated Ballistic Identification Network (NIBIN).

With IBIS/NIBIN (as it now stands), the computers do a rough comparison of bullet and breech-face characteristics with those in the crime-evidence database and select images within the general “class characteristic” range, leaving the firearm examiner to look for a potential match of individual characteristics. If there is a probable match, the actual fired evidence is requested for a microscopic comparison to a suspected crime firearm.

This is a valuable system utilizing the latest in computer technology, and it has proven an effective means of linking criminals to crimes through guns used in various, often distant locations. It is currently in use to compare crime-scene evidence exclusively.

Alas, there is always someone who will take a great idea and corrupt it. Such is the case with the idea to enter every new handgun into this database.

What’s wrong with the notion of adding non-crime guns to the mix? The short answer is: just about everything. This plan was actually implemented in New York and Maryland. And after more than five years in operation, neither system has been responsible for a single conviction.

As a firearm examiner, I know about 50 methods that smart—and even not-so-smart—criminals could use to bypass or defeat such a new-gun “fingerprinting” database. And even beyond that fact are the following issues:

1. “Ballistic fingerprinting” relies on entering a single fired cartridge case and bullet from each new gun into the database. While cartridge-case impressions vary little over the life of a firearm, striae on bullets change over time as barrels wear.

2. Bullets and cartridge cases are made of a variety of materials. This radically affects the quality of bullet striae and firing-pin impressions that will result. Some bullets take poor rifling impressions. A few take no matchable impressions. Additionally, the quality of firing-pin impressions varies considerably depending on the primer. This involves the primer cup and, with rimfires, the cartridge case. Primer cups on centerfires are made of gilding metal (a soft copper alloy), brass, nickel-plated brass and steel. These materials vary in hardness, and the variations can present serious matching problems even with cartridges of the same make.

In a California Department of Justice study, 50 fired cases from the Federal Cartridge Corp. were compared. The cartridges had all been fired in the same gun. In microscopic examination by “experts,” 38 percent were missed! When different cartridge makes were added to the mix, still all from the same gun, 62 percent were missed. Obviously, this presents a serious problem with only one fired case or bullet from each gun.

| In view of scientific findings and societal issues, I see absolutely no merit in systems where the cost-to-benefit ratio is so high. |

Beyond different makes of cartridges is the issue of different loads in the same cartridge. Heavier loads generate greater pressures and deeper, clearer impressions than light loads. To even have a chance of being useful, the system would have to image all the possibilities, or hope the criminal in question used the same type and loading of cartridge used for the “fingerprint” sample.

3. Barrels, firing pins, slides, bolts and similar parts affecting these marks can easily be replaced or altered. Without a system to “register” gunsmithing work, marks would become impossible to match.

4. Many firearms can fire a variety of ammunition other than the type for which that particular firearm was originally chambered. How could these be accommodated into the system?

5. Conversion kits for various firearms are available to permit use of a different caliber of ammunition. Currently, these are not classified as “firearms” and are sold via mail.

6. If every gun was entered—all 250 million or more—with only a tiny fraction being used in crime (according to DOJ statistics), and even fewer actually fired in commission of a crime, such a system would constantly collect and sift huge amounts of irrelevant data.

The first online computer system for comparing images of bullets and cartridges was called “DrugFire.” It took five minutes to put an image online and another five to get a response—a 10-minute turnaround.

The current (IBIS/NIBIN) system contains many more items, as it has been improved and expanded by virtue of a greater variety of images available for each piece of evidence. There are also more subscribers online. Currently, this nationwide system has 238 sites with 14 servers. The servers import information every four to six hours. The time to retrieve results for a particular request takes about six hours.

Note that this system is limited to those firearms used in crimes. Consider the time factor in adding images of every new handgun or every new gun, let alone trying to get all existing guns added.

Considering the above difficulties, there would undoubtedly be many false hits in attempting an identification of any gun used in a crime. The turnaround period would increase exponentially. Plus, such a system would be very expensive. Who would pay for it?

Not surprisingly, “ballistic fingerprinting” of guns not used in a crime has never really taken off. Enter two new proposals—“microstamping” and “bullet serialization.” In brief, these systems replace evidence imaging with an alphanumeric, and possibly a bar and dot code, identification system.

Microstamping proposes engraving the serial number and manufacturer information on the firing pin or other parts of each firearm. Thus, the gun would supposedly stamp the information on every cartridge fired.

|

Why Microstamping and Bullet Serialization Won’t Work |

It’s important to note that equipment for bullet/cartridge collating is not only non-existent, but is incompatible with the current method of ammunition manufacture. Estimates from ammunition manufacturers for implementing such a coding system are a cost increase from the current price of a few cents per cartridge to several dollars. |

“Bullet serialization” proposes a laser-engraving system to place an engraved code on the base of every bullet. A matching code would be engraved on every cartridge case in which that bullet is seated. Every box of ammunition would contain cartridges coded to that box.

These systems are currently under consideration in 18 states, with the immediate focus on handgun ammunition and so-called “assault rifle” ammunition.

Proponents of these systems claim that the earlier cumbersome plan of cartridge case and bullet imaging would be gone, along with the problems of primer or cartridge case and bullet material affecting the quality of crime evidence. Each fired case would be matched to its gun or each bullet/cartridge case would be code-stamped to a particular box

of cartridges.

|

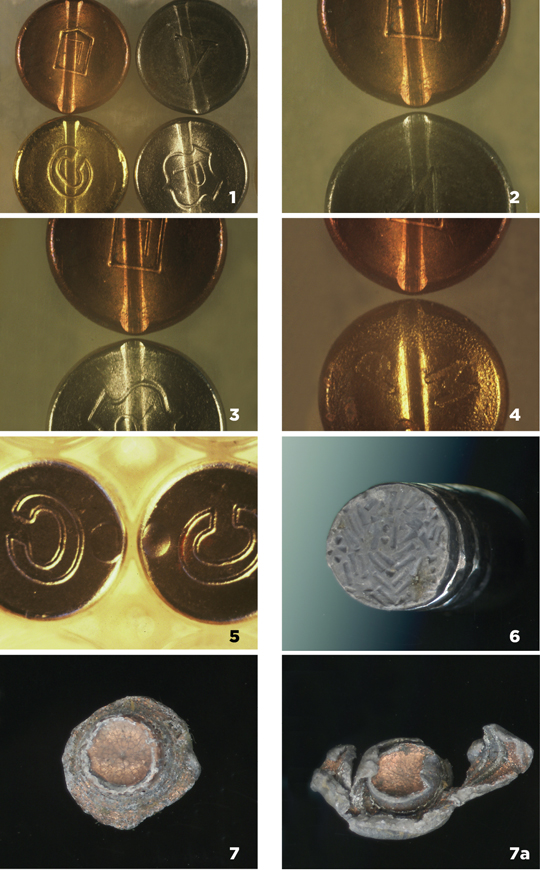

| 1. The firearm examiner’s primal question: Same gun or different? As with primers in centerfire cases, rimfire cases are made of copper alloy, brass, nickel-plated brass and steel. Softer cases and primers pick up more detail than harder ones. These are from the same gun producing a “bar” impression on .22 LR cases. 2. Steel cases pick up far less information than soft copper alloy. Best impressions are at the case rim. 3. In a like manner, nickel-plated brass cases yield a more shallow impression. 4. Irregularities in manufacturing on this brass case masks firing pin markings. No current technology exists to engrave rimfire firing pins. 5. Same gun or different? Round ends on rimfire firing pins (the small impression) give poor ignition. Stoning a flat profile cured this problem. It took about five minutes. Needless to say, this would remove a code number. 6. On firing, certain types of powder will stipple a lead alloy bullet or core in an FMJ type, obliterating a code number. Example is a .45 caliber bullet. 7, 7A. Copper plating on lead bullets tends to crack with heat and pressure. A micro-engraved code might survive firing in a “best case” scenario. The two examples seen here are about average for .22 LR. Bigger bullets with bigger engravings might fare better. |

The speed of crunching numbers would supposedly be far faster than sifting through characteristics in series of images. And more individual firearm data, they claim, could be processed faster.

Yet taking a look at these systems individually, there are many reasons each proposal won’t work. Let’s look at each scheme individually.

Microstamping Microstamping would transfer data from the firing pin to its impression in the primer and possibly similar engraved data on the breech face of the firearm, stamping it on the primer area surrounding the pin impression or on the case head, respectively. From a mechanical perspective, the firing-pin engraving system (using a metal-etching laser) has been demonstrated. Micro-engraving would simply create numerical “imperfections,”

as it were.

This system is the law in California, and will go into effect in 2010. It will be applied to new models of semi-automatic handguns only. One company, NanoMark Technologies, holds the patent and is the sole source for the process. Stamps are

25 microns in depth, with a micron being 1/1000 of a millimeter. In the tests conducted at the University of California at Davis, alphanumeric codes often survived 2,500 firings, but marginal dot and bar codes did not.

While few changes occur with normal use of a firing pin, obliteration of any marking is a simple matter of a few passes with a file or sharpening stone, or peening with a hammer. Additionally, the laser-engraving process involves heating the firing pin nose. This, in effect, anneals the point, softening it and rendering it more easily deformed by use.

Certain makes of semi-auto pistols, in their ejection, produce what are known as “drag marks,” which is to say that as the case is ejected, it pivots on the point of the firing pin, grinding the originally round impression into a slight oval. This would seriously degrade, if not obliterate, such a stamp mark, though striae left by this drag could be used

for comparison.

Also, firing pins in many arms are easily replaced. Microstamping would, therefore, require a registration system in which firing pins would be treated like firearms. In light of this, it should be added that the manufacture of many types of firing pins is a rather low-tech operation. Therefore, replacing the serial-engraved firing pin is a fairly simple operation, far easier than removing a firearm serial number.

Breech face stamping of a serial number would be problematic, affected by primer hardness and pressure as the usable area is the margin surrounding the firing pin hole. Additionally, some primers are stamped with trademark or other codes, which occupy some of the available space. Voids created by this stamping would likely obliterate portions of a serial number unless it was there in multiple repetitions. In such a case, these numbers would be exceedingly small and shallow. Primer hardness and other surface issues would further confound identification.

With rimfire ammunition, since cartridges operate at low pressures, trademark information stamped on the case head would create voids where pin impressions would leave only partial numerical information. Rimfire pins produce impressions far smaller than centerfire pins.

The cost of implementing microstamping firing pins of a conventional sort could add an estimated $200 or more per firearm, according to the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI). To discourage obliteration, such pins would require either a coating or tip made of something akin to a diamond to overcome tampering. Additionally, they would have to withstand sudden shocks without breaking. Such pins would well exceed the $200

mark. And while diamonds can be micro engraved, they

don’t withstand sudden shocks. In reality, no technology currently exists to make such a pin.

Bullet Serialization This scheme proposes engraving serial codes on individual bullet bases and cartridge cases. Russ Ford, who speaks for Ammunition Coding Systems (the proprietor of this technology), claims this coding is simply the extension of the system of coding and tagging used by the beverage industry to mark the billions of cans of beer and soda sold every year. According to Ford, up to 27 characters can be engraved on the base of a 9 mm bullet.

“Anyplace you can shine a light, you can laser a mark,” Ford said in an e-mail to this author.

This engraving process exists only as an individual unit owned by the company. Bullets and cases would have to be matched in the loading process. Currently, there is no such technology in the ammunition industry to permit this collation. To do so would require rebuilding all the nation’s major ammunition manufacturing plants. This coding would be complicated by the fact that, for quality-control purposes, batches of cartridges are continually removed from the production line for testing and evaluation. Defective and potentially defective ammunition is similarly removed through both automated and visual inspection. Packaging would have to be a hand operation. One lost or misplaced cartridge would render a box forensically useless.

| Barrels, firing pins, slides, bolts and similar parts affecting these marks can easily be replaced or altered. Without a system to “register” gunsmithing work, marks would become impossible to match. |

The proposed system would engrave the bullet base and presumably the interior of the case, since exterior engravings would be scrubbed and likely obliterated by many types of firearm actions. Engravings on soft-point or total metal jacket bullets might work, as these bases are of copper or gilding metal and will survive almost any shooting incident—the exception being a high-velocity impact with something on the order of an armor plate or concrete resulting in complete fragmentation. Engraving on full metal jacket bullets having an exposed lead core at the base would be more problematic. Granules of ball powder or tubular powder impact the lead core and stipple the surface to a considerable degree, obliterating any fine detail that was there prior to firing. This would leave only the margin of the jacket for engraving that might survive.

With a lead-alloy bullet, chances of engraving survival are far worse. Those operating at low pressure in ammunition loaded with fine, flake powder might survive with engravings intact, but little handgun and no centerfire rifle ammunition is loaded that way—at least that I am aware of. Upon firing, the copper plating found on much rimfire and revolver ammunition has a tendency to flake and crack, much like mud in a drying puddle. Such surfaces do not retain rifling striae well. Micro engravings would likely fare no better.

Additionally, other coatings used on bullets would present their own problems. Frangible bullets, designed to fragment on impact, would retain no information. Shotgun pellets could not be coded.

It’s important to note that equipment for bullet/cartridge collating is not only non-existent, but is incompatible with the current method of ammunition manufacture. Estimates from ammunition manufacturers for implementing such a coding system are a cost increase from the current price of a few cents per cartridge to several dollars.

Ammunition manufacturing is a highly automated, high-volume, low-margin business. How could the industry be expected to survive such demands? There is also the safety issue of firing metal-etching lasers in close proximity to explosive primers and smokeless powder, while also vaporizing lead.

Implementation of such a system would also, of course, take us back to the bookkeeping of the early days of the Gun Control Act of 1968, when buyers had to sign a register for every box of cartridges purchased. The new recording system would require entering the coded information into a database on a per-buyer basis. With number-crunching under the best of scenarios (50 coded rounds to the box), it would be necessary to track 240 million boxes of cartridges per year.

Many other questions exist. How would the system deal with stolen ammunition? How would it deal with lost or abandoned ammunition? How would it deal with transferred ammunition? How would it deal with reloaded ammunition? What about coding imported ammunition? Finally, who would create and run this database to guarantee there was no misidentification at the source or at the point of sale, and at whose cost? Clearly, this would have to be implemented at a national level, not at the state level, which is central to many current proposals.

Societal Issues At the head of the larger social concerns would be the key question: What about all the guns and ammunition currently in circulation—250 million firearms and untold billions of rounds of ammunition? Current production figures are estimated at about 12 billion rounds per year. DOJ statistics indicate that most firearms used in crime are on average seven to 10 years old, and about 80 percent are stolen or obtained from friends or family. These can only be traced to their last legal owner.

Guns given reasonably good care can last a long time. I own two that are 120 and 128 years old, respectively. These guns work just as well now as they did when they were made. How long would it take for a microstamping system to start making an impact on the universe of crime guns?

Ammunition lasts a long time, too. I have fired cartridges well over 100 years old that worked quite well. An acquaintance in the forensic field told me of two cases he encountered involving homicides using Civil War arms and cartridges.

And what about handloaded ammunition? No coding system could deal with this.

In practice, all existing arms/ammunition could simply be considered “contraband” and subject to seizure by law enforcement, as many state “bullet serialization” bills would require. However, a federal law of this sort was tried with alcoholic beverage manufacture and possession during the years 1920 to 1933, and it didn’t work. This law had the unintended consequence of acting as the primary catalyst in the sudden creation of a vast empire of organized crime. What assurance do we have that the creation of a huge pool of illegal arms and ammunition would not produce a similar outcome?

While not known for their intelligence, many criminals (like many of the rest of us) watch such television dramas as the “CSI” series, where they pick up bits of information useful for their trade. Cartridge cases are excellent crime-scene evidence. Some criminals have taken to eschewing semi-autos in favor of cartridge-retaining revolvers. They often pick up their fired cases. Some have even begun seeding crime scenes with cases collected from shooting ranges, scrap boxes or other places where they accumulate.

Lastly, if semi-auto handguns are the only ones to be engraved, American criminals would likely follow the Canadian practice of weapon substitution. With government gun control measures creating a scarcity of handguns, felons there switched to rifles and shotguns for their needs. These are frequently altered to handgun-sized weapons, and many have more power than handguns.

While I and others in my field, along with firearm and ammunition manufacturers, favor real advances in fighting crime, we want proof that proposals are genuine advances. Yet the National Research Council (NRC), part of the National Academy of Sciences, and U.C. Davis have both tested and evaluated the proposed systems and found the technology to be unreliable. The preeminent professional organization in the field—the Association of Firearm and Tool Mark Examiners (AFTE) has yet to be asked to do a peer-reviewed study of these technologies.

Even under the best possible technical outcomes, consider this fact: Only a small fraction of guns are used in a crime, and even more rarely is the gun fired in commission of the crime. These proposed systems would have to process incredible amounts of irrelevant data—in effect seining an entire ocean to catch a few sharks.

In view of scientific findings and societal issues, I see absolutely no merit in systems where the cost-to-benefit ratio is so high. As a society, we would do better to focus on criminal gun use—putting more resources into crime laboratories and the training of forensic scientists—than creating cumbersome schemes to inconvenience law-abiding gun owners and wreak havoc among firearm and ammunition manufacturers.

More Like This From Around The NRA

More Like This From Around The NRA