by Dave Kopel

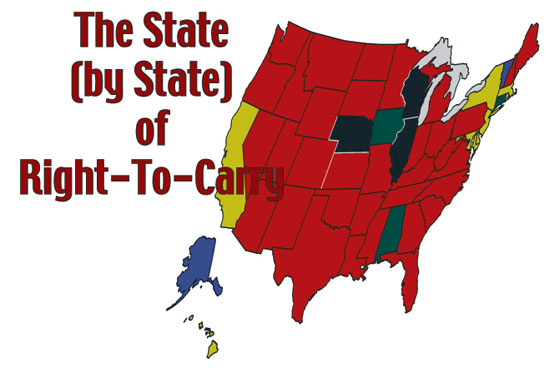

Thirty-eight states? Thirty-nine? Forty? We attempt to resolve the states of confusion by giving you all you ever wanted to know about the status of Right-to-Carry laws but were afraid to ask.

In spring 2006, the Nebraska legislature defeated a filibuster and passed a Shall-Issue law for licensing the carrying of concealed handguns by adults who pass a background check and a safety class. Nebraska’s governor signed the bill into law.

Just a few weeks earlier, Kansas Gov. Kathleen Sebelius had vetoed a Shall-Issue bill, then the Kansas legislature overrode the veto. Thanks to the hard work of pro-rights activists in Kansas and Nebraska, there are now 40 states that allow law-abiding citizens to carry handguns for lawful defense, and a grand total of 48 that allow at least some citizens to do so.

Here is the state-by-state status report:

No permit needed: Two states—Alaska and Vermont—do not require a permit for any adult who is legally allowed to possess a firearm. Alaska will issue a permit, however, upon application. An Alaskan might want to obtain a permit from his or her home state in order to use the permit to carry in another state, as is allowed by many states under the principle of “reciprocity.”

Shall-Issue: Thirty-five states, including all states not listed elsewhere, practice Shall-Issue permit distribution. Nebraska and Kansas are the newest additions to this category. As with a driver’s license, a Shall-Issue law states that the government “shall” issue a concealed handgun carry permit to a person who meets certain objective criteria, such as: being above a minimum age, passing a background check and, in some states, passing a safety class or test.

Do-Issue: Three states—Alabama, Connecticut and Iowa—have statutes that are not completely Shall-Issue, but that reserve some discretion to the issuing law enforcement agency. In these states, local law enforcement will generally issue a permit to the same kinds of persons who would qualify for a permit in a Shall-Issue state, and many times these states are included on Shall-Issue state lists.

Ten states generally do not allow such handgun carrying in public areas or only allow limited permits:

Capricious-Issue: Eight coastal states have permit laws but give local law enforcement almost unlimited discretion to deny permits. Although there can be significant variation from one locality to another, permits are rarely issued in most jurisdictions, except to celebrities or other influential people. These Capricious-Issue states are Hawaii, California, Delaware (not as bad as the others, in practice), Maryland, New Jersey (the worst), New York, Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

No Issue: Illinois has no process for issuing Right-to-Carry permits. The state does, however, allow certain persons—such as law enforcement or security guards—to carry without a permit. Likewise exempt is carrying a gun in one’s home or place of business.

Wisconsin is the other No-Issue state, and its law is even more extreme than Illinois. In Wisconsin, the Right to Carry is outlawed under all circumstances, even in one’s home or business premises. However, a decision of the Wisconsin Supreme Court, interpreting Wisconsin’s state constitutional right to arms, held that in most cases the ban cannot be enforced against people who carry on their own property.

The Wisconsin legislature has twice come within one or two votes of overriding the governor’s veto of a Shall-Issue law. Historically, in every state where Shall-Issue laws have been blocked by a veto (such as Florida and Colorado), a Shall-Issue law has eventually been enacted. So Wisconsin will almost certainly become a Shall-Issue state—as soon as Second Amendment supporters there elect a new governor, or even just a couple more good legislators.

The prospects for reform in Delaware are also good. Shall-Issue legislation there has enough co-sponsors to pass both houses.

Rhode Island actually has a Shall-Issue law (for issuance by local law enforcement) and a Capricious-Issue law (for issuance by the attorney general). The attorney general has succeeded, at least temporarily, in stifling the local Shall-Issue system, but a decision of the Rhode Island Supreme Court suggests that this state of affairs is untenable. All that is necessary to implement Shall-Issue in Rhode Island is a new Attorney General with a different attitude. (My Albany Law Review article, available at www.davekopel.org, provides more details about Rhode Island and Wisconsin.)

Of the remaining seven holdouts, three states—New York, Illinois and California—have previously passed a Shall-Issue bill through a single house of the legislature. The passage suggests that Shall-Issue, although hardly easy to enact into law, might eventually be accomplished. In all seven of the final holdout states, it would appear that it would be very difficult to ever pass a Shall-Issue law by a wide enough margin to override a veto. But with legislatures, you just never know.

The more states that enact Shall-Issue laws, the more legislators in holdout states become open to the idea that Shall-Issue is not dangerous, as some continue to argue. Ohio, Minnesota and Michigan are examples of states whose enactment of Shall-Issue legislation was possible only because so many other states had acted previously. As the number of Shall-Issue states rises, so does the possibility of enacting Shall-Issue in the dwindling number of holdouts.

As momentum builds in a given state, a Shall-Issue bill eventually attracts the support of all or almost all Republican legislators, and of almost all Democrats with a c rating or higher from the National Rifle Association. Many of the swing votes (the c-rated legislators, who say that they are pro-Second Amendment, but who often vote for gun control laws) are attracted by the objective standards of the Shall-Issue system, which, unlike the Capricious-Issue system, typically forbids gun carrying in certain places (e.g., hospitals), sets objective standards about who may not receive a permit (persons with various disqualifying conditions), and (in most states) requires a specific amount of firearms safety training.

Of course, the most important effect of Shall-Issue laws is that licensed handgun carriers are able to protect themselves or other innocents from violent felons. But there is also an important cultural effect: the enactment and continuing existence of Shall-Issue laws help educate the public—including citizens who do not own guns—that defensive gun carrying by responsible citizens is a highly legitimate activity that is appropriate in almost all public places.

More Like This From Around The NRA

More Like This From Around The NRA