by Wayne LaPierre

When 78 million Brazilians went to the polls Oct. 23 to vote down a referendum calling for a ban on the sale of all firearms and ammunition, it was a resounding “no!” heard round the world.

Over 67 percent of the total electorate of Brazil were saying decisively that they’d had enough. The national referendum—the first ever in Brazil—had been touted by the world “gun control” movement as the next step toward what they dream of as total civil disarmament.

Globalist billionaire George Soros’ protégé, Rebecca Peters, the self-proclaimed queen of “civil disarmament,” saw the referendum as a global model.

“If the ban is passed, then I definitely expect other countries to try the same thing,” she told The Washington Post. Peters, who heads the International Action Network on Small Arms (IANSA), is deeply committed to a worldwide ban on firearms owned by civilians. Millions of dollars from such groups and from direct and backdoor United Nations organizations were funneled into Brazil to press for the gun ban referendum.

Stunned by the results of the referendum, The Washington Post whined that, “The defeat disheartened gun control proponents,” and quoted a Brazilian source as saying, “I hope the whole world will be able to deal with this again.”

The actual question placed before voters was simple enough: “Should the sales of arms and ammunition be permitted in Brazil?” Thanks to the efforts of a handful of men and women who have created an obviously effective pro-gun grassroots effort out of whole cloth, the Brazilian people understood that the ban was another step toward leaving them defenseless against the anarchy of violent crime beyond any control of police.

The referendum was the creation of people like Peters bankrolled by nations, foundations, rich individuals and by the United Nations.

October’s national referendum was the first ever in Brazil, a nation that has compulsory voting for an estimated

120 million registered adults. It is conserv-atively estimated that the referendum—the process of handling all those voters at their polling places and counting the ballots—will cost in excess of $200 million (U.S.). This is more than double the amount Brazil spends annually to service all levels of police for the entire naIANSAtion.

Where the sale of firearms is minimal, the question of an ammunition ban is of considerably greater importance. Under current law, Brazilians are already limited to buying ammunition only for registered guns. Yet sources in Brazil say the real result of the ammo sales ban would undoubtedly be a healthy new submarket in an already-flourishing black market.

The details of the loss of freedom of ordinary firearms owners in Brazil first became reality in December 2003 when the Brazilian National Congress enacted a new law that people like IANSA’s Peters say merely “regulates firearms.” The law—“The Statute of Disarmament”—created a draconian system of universal firearms registration and gun owner licensing, all compounded with substantial fees beyond the incomes of a majority of Brazilians.

To get a license to continue owning a firearm under the new law, an ordinary citizen has to prove psychological fitness; undergo a background check in which even having ever been sued in civil court is a disqualifier; must prove “legal employment”; and provide “proof of technical capacity” to handle firearms. A firearms owner must also present an approved reason to own a gun. Keep in mind that under existing laws, Brazilians were already limited in the number and types of guns they could own or buy.

Under “The Statute of Disarmament,” with a registration fee of R$300 per gun, and an equal amount for re-registration every three years or for replacement of a lost registration certificate, the cost alone made compliance impossible for millions of formerly law-abiding and peaceable Brazilian gun owners. The average family income ranges from R$900 a year in rural states to as high as R$5,000 in affluent urban centers. For a gun owner sustaining his family on $900 a year, the registration fee for one gun would be a full one-third of his annual income.

For ordinary Brazilians fearful that continued gun ownership would make them criminals, the government created an amnesty period during which people could give up their guns and receive between $50 and $150 compensation, regardless of the actual value. After that, firearms possession without registration and licensing became a no-bail criminal offense.

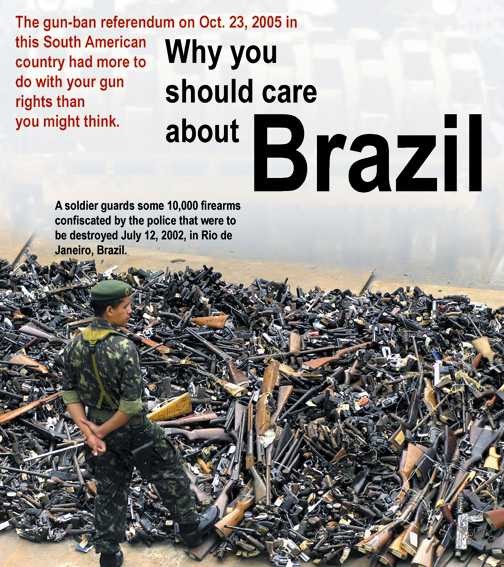

Among the more alarming strictures of the 2003 law is a requirement that guns seized by police be destroyed within 48 hours. With all of this, millions of legally owned guns, mostly common sporting arms, have become “illicit small arms”—the U.N. phrase for contraband.

In Brazil, there has been an orgy of gun burnings and crushings, with gun confiscation advocates joyously participating. Imagine, if you will, the likes of Sarah Brady personally presiding over the destruction of your grandfather’s Winchester Model 12.

Unlike other gun confiscation schemes in Canada or Australia or England, this one was not aimed at any particular type of demonized firearm. This confiscation targeted all guns in private hands.

All of this came only with massive financial assistance from the “global disarmament” community, and propaganda from those who control the airwaves in Brazil. Since voting is compulsory, and with Brazil having huge numbers of illiterate people, television aimed at that very unsophisticated audience has been a major factor.

Brazil’s soap operas—with very devoted audiences among the poor—have beat an endless drum for gun control, first for the 2003 law, and then for the gun ban referendum. A story in the U.K. Guardian, centered on a protest march in Rio demanding passage of “The Statute of Disarmament,” touted the effectiveness of daily-dramatized propaganda:

“The protest had been heavily promoted in the soap opera ‘Women in Love.’ For weeks, the show’s characters have talked about the march, and their presence guaranteed a large turnout despite the weather.

“The popular soap opera, which threads together the stories of several women, has hit hard on the issue of gun violence in recent weeks. A scene where a character was killed by a stray bullet was front-page news last month, eclipsing many real killings.”

All of this occurred with largely invisible but substantial help from the United Nations, and very visible help from church groups representing a new version of “Liberation Theology,” like the World Council of Churches, all allied directly or indirectly with Peters’ IANSA.

With respect to the referendum, Brazilian election law officially controls the airwaves. The government—through the Federal Elections Board—strictly regulates access to broadcast media. Much of the news media in Brazil was pressed into service promoting passage of the referendum.

In her interview with The Washington Post, Peters predicted that a win for the referendum gun ban would have reverberations around the world. “It will send a message to other countries influenced by powerful gun lobbies that it’s possible to work around them,” she said.

Where the government controls the officially recognized political messages, there is no such restriction on the media.

A year before the official campaigns for and against the referendum were allowed to begin, unesco, through the U.N. International Programme for the Development of Communication, provided significant funding to influence the outcome of the vote through a grant that, “aims at increasing the quality and quantity of coverage … in the lead-up to the 2005 gun ban referendum …” Among the specifics was a cadre of organized and trained “women from affected communities to build capacity for media advocacy and develop skills for working with journalists from all media …”

The recipient of this largess was Viva Rio, which the unesco funding documents said, “coordinates peace campaigns and community-based projects … through a network of over 500 local partners. Viva Rio also coordinates national and regional campaigns, including a women’s disarmament campaign called ‘Choose Gun Free! It’s Your Weapon or Me,’ and other projects and research programmes on disarmament in Brazil … News and information web sites developed and hosted by Viva Rio will facilitate networking and communications …”

In reality, Viva Rio is the 800-pound gorilla (or more accurately, guerilla) in the war against gun ownership in Brazil. Its English language web site boasts a single-minded goal: “To reform permissive and inefficient legislation on arms control, seeking to end civilian use of firearms.”

Among its “disarmament” efforts are “Public awareness campaigns on the need for civil disarmament,” so that “‘honest citizens’ and their families do not become victims of their own guns in accidents or do not fall victim to armed assailants if they try to defend themselves with a gun.”

And what do they offer “honest citizens” in place of armed self-defense? Viva Rio trades all that “in favor of a culture of peace (through the peaceful resolution of conflicts between individuals) …” (Parentheses in the original.)

They actually want honest Brazilians to defend themselves against murderous armed drug gangs by simply submitting. This might be funny were these gun-banners not extraordinarily successful. The key to their power is international money, connections and the means to disseminate their propaganda.

By its own description, the ngo says, “Viva Rio is funded by the public sector (federal, state and municipal governments), the private sector (national private companies and multinational corporate organisations), foreign government development agencies (e.g. DFID of the UK government and DFAIT of the Canadian government), donor foundations (e.g. Ford Foundation), ngos (e.g. Save the Children Sweden) and international agencies (e.g. UNESCO and UNICEF).” (Parentheses in the original.)

An article published by another ngo called South North Network Cultures and Development touted Viva Rio as “fully autonomous … It gets state and municipality subsidies and is increasingly self-sufficient thanks to its own profit-generating activities, e.g. the insurance brokers company, the microcredit bank, etc. Business is sponsoring its activities …

“Viva Rio is a brilliant example of a lively social and cultural movement engendered by civil society … In this sense, it is a deeply democratic movement. Yet it is not reduced to U.S.-inspired democracy, based on individualism …”

For all of the ngos involved in the Brazil civil disarmament movement, there is one ultimate end worldwide—to bring all of this to our shores. It is Peters’ and George Soros’ ultimate dream.

|

“I’m still feeling I’m dreaming. You could not believe the civic atmosphere of this country in the last days. It was a historical victory against the government and media lies.”

Luciano Rossi, managing director of Brazil-based Rossi Firearms and a leader of the Brazilian pro-gun movement. |

As part of the lead-up to a concerted United Nations effort in June 2006 to create an international treaty to disarm civilians worldwide, a meeting of gun ban ngos was held in Rio de Janeiro in March 2005. The theme was private possession of firearms, and any group or individual in support of civilian ownership of arms was specifically excluded. This is U.N. democracy at work.

A key paper presented at that meeting was a manifesto against gun ownership in the United States. Titled, “The regulation of civilian ownership and use of small arms,” the document declared that the “u.s. public holds one-third of the global gun arsenal: an estimated 234 million guns …” and claimed that “the permissive and massive legal market for small arms in the United States is a major source of illicit firearms throughout the western hemisphere.”

Chief among its recommendations was that global “awareness raising campaigns could help all societies move from a culture of ‘rights’ for weapons owners to one of ‘responsibility’ for ensuring that society is not harmed with their weapons.” (Emphasis added.)

“And ensuring that society is not harmed with their weapons, means that those firearms are banned, taken and destroyed.”

Destroying a “culture of rights.” That, indeed, is their goal.

In the conclusion, their paper says:

“Along with weapons collection, however, it is critically important that appropriate regulatory regimes be implemented to establish norms of non-possession …” Of course, “norms of non-possession” means nothing less than abolishing the right of private firearms ownership.

For all of this, Brazil was supposed to be just another step. But it didn’t happen that way. The majority of the people of Brazil did what the global gun-ban crowd assumed was unthinkable. They stood up for their liberty and for the security of themselves, their families and their communities. They stood up for the most basic human right of all—self-protection.

More Like This From Around The NRA

More Like This From Around The NRA